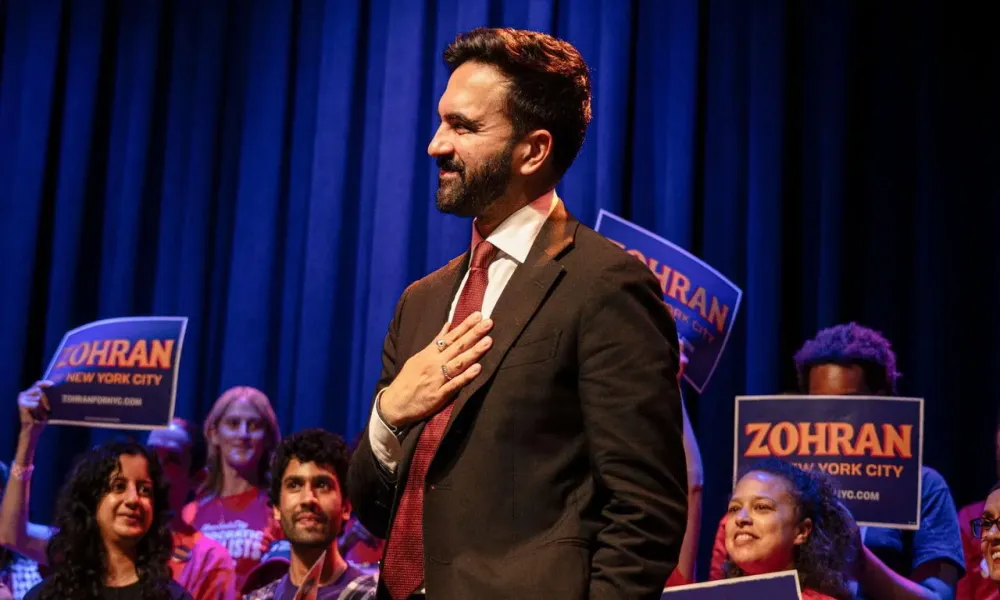

When Zohran Mamdani rose to prominence through a campaign centred on rent, transport, childcare and the everyday cost of living, the story was often told as a United States, or rather, a New York anomaly. A young, openly democratic socialist winning in one of the world’s most expensive cities. However, Mamdani’s success fits into a wider political rhythm that has defined the past decade across democracies, including Cyprus.

His campaign story is about political cycles, overcorrections, and a growing sense among voters that the system no longer delivers stability, affordability, or meaning. As Costa Constanti puts it, “politics today doesn’t move forward in a straight line, it swings hard from one extreme to the other.”

The analysis that follows draws on an interview with Constanti, a political analyst, consultant and candidate running with Volt Cyprus in the upcoming elections, who situates Mamdani’s rise within a broader global and local political shift.

Politics by overcorrection

One of the clearest patterns in contemporary politics is pendulum swings in the place of ideological continuity. Progressive moments are followed by conservative backlash, which in turn produces another corrective shift. The United States has moved from Barack Obama to Donald Trump, then to Joe Biden, and back again to Trump. Similar reversals play out globally, with different faces and institutions.

According to Constanti, this pattern has less to do with individual leaders and more to do with voter behaviour. “What usually happens is that people in power get comfortable, their voters relax, and they don’t show up to re-elect them,” he says. At the same time, opposition voters are mobilised by frustration, often intensified by media narratives that amplify conflict. Elections become instruments of punishment rather than affirmation.

Mamdani’s rise, in this reading, is not exceptional. It is a corrective response to political fatigue, part of what Constanti describes as a cycle of “overcorrections driven by disappointment.”

Disillusionment with the system

What distinguishes the current moment, Constanti argues, is that public anger increasingly targets the system itself. Many voters feel that institutions remain fundamentally unchanged regardless of who holds office. “People don’t just blame the leader anymore, they blame the whole structure,” he notes. Leaders rotate, but lived conditions do not improve.

This produces a paradox. Politicians are attacked before they can govern, while simultaneously being expected to deliver immediate results. Under such pressure, leadership drifts toward populism, simplified messaging, and a constant performance dance with voters. “Leaders end up selling success before they’ve had the chance to do the work,” Constanti says. Success must be marketed continuously, often before it materialises.

Democratic socialism, as articulated by figures like Mamdani, attempts to break this cycle by reconnecting politics with concrete outcomes. The promise is relief through practical and tangible solutions to everyday problems.

A culture war society

Constanti also frames the past decade as the emergence of a full-scale culture war society. Political debate now unfolds in a shared digital arena where local and global actors coexist. A mayor in New York can feel almost as relevant to voters in Cyprus as a mayor in Nicosia, largely because of the proximity created by social media.

“We’re all sharing the same political space now,” Constanti says. “The BBC, CNN, a local mayor, a random user on social media, they’re all competing on the same platforms.”

This globalisation of political discourse has clear benefits. Ideas circulate faster, comparisons become easier and citizens are exposed to alternative policy models. But it also carries risks. Local issues can be eclipsed by imported conflicts, attention fragments and politics becomes reactive rather than rooted.

Cyprus, Constanti notes, is fully embedded in this environment. “A change in Cyprus might not affect the world,” he says, “but a change in the world will definitely affect Cyprus.”

Democratic socialism, rearticulated

Importantly, the ideas now framed as democratic socialist are not foreign to Cyprus. Concepts such as direct democracy, social justice, transparency and anti-corruption have long histories on the island.

What is new is the way they are communicated. The language is sharper, the platforms digital, the framing generational. Instead of abstract ideology, the focus is on everyday pressures like rent, wages, transport, housing and energy costs.

Mamdani’s campaign exemplifies this shift. It treats affordability not as a personal failure but as a political responsibility. That framing, Constanti argues, “travels very easily, because people everywhere are feeling the same pressures.”

Cyprus, but structurally different

Despite shared pressures, Cyprus operates under different institutional constraints. Municipal powers are limited. Fiscal space is narrower. European Union frameworks shape national policy. Coalition politics and entrenched party structures slow experimentation.

At the same time, Cyprus’ small scale imposes a degree of restraint. Politics cannot afford total fragmentation. Cooperation remains a necessity. “In Cyprus, you can’t completely tear each other apart,” Constanti says. “We’re a small society, we know each other, and that creates natural limits.”

Progressive politics in Cyprus, he argues, must work within these constraints rather than pretend they do not exist.

Progressives, populists, and political fatigue

Constanti draws a clear distinction between progressive politics and populism, even when rhetoric overlaps. Traditional parties, he argues, have struggled to adapt to contemporary political realities. Some have drifted toward populist tactics in an effort to remain relevant, often damaging their credibility.

Hard populist forces, meanwhile, have gained ground through emotionally charged narratives, particularly around migration, without demonstrating an ability to deliver solutions. “They win the narrative,” Constanti says, “but they don’t deliver.”

Ultra-populist figures thrive on attention and provocation rather than policy depth. In this environment, newer political formations attempt to fill a credibility gap by emphasising expertise, transparency and delivery. Their appeal is genuine, especially among voters disillusioned with stagnation. But the risk is equally real. Freshness without results quickly turns into disappointment, and disappointment feeds further radicalisation.

In search of meaning

Stripped of ideological labels, the concerns driving political change are consistent. Constanti identifies them as the cost of living pressures that dominate daily life, salaries that lag behind prices, housing that has become increasingly inaccessible, climate stress, water scarcity, pollution and high energy costs. Education systems feel outdated, migration debates are often misdirected, obscuring deeper economic drivers. Cyprus’ identity and tourism model remain unresolved, while the Cyprus problem itself risks being reduced to slogans rather than addressed seriously.

“These are the issues people actually care about,” Constanti says. “Battles that affect their lives every day.”

These are precisely the areas where progressive politics claims relevance. Constanti argues that this responsibility increasingly falls to new political formations like Volt Cyprus. The aim, as he explains, is an attempt at reconnecting governance with material reality.

A moment of possibility, and risk

Mamdani’s rise illustrates why democratic socialism is regaining visibility. It speaks to a desire for politics that delivers measurable relief and restores trust in public capacity. But it also highlights the dangers of inflated expectations in an era of institutional fragility.

For Cyprus, the lesson is to recognise that voters are searching for credibility, competence and honesty about limits. Progressive politics can be refreshing. It can also be dangerous if it raises hopes it cannot meet.

“The pendulum will swing again,” Constanti says. The question is whether the next correction will be constructive, or corrosive.